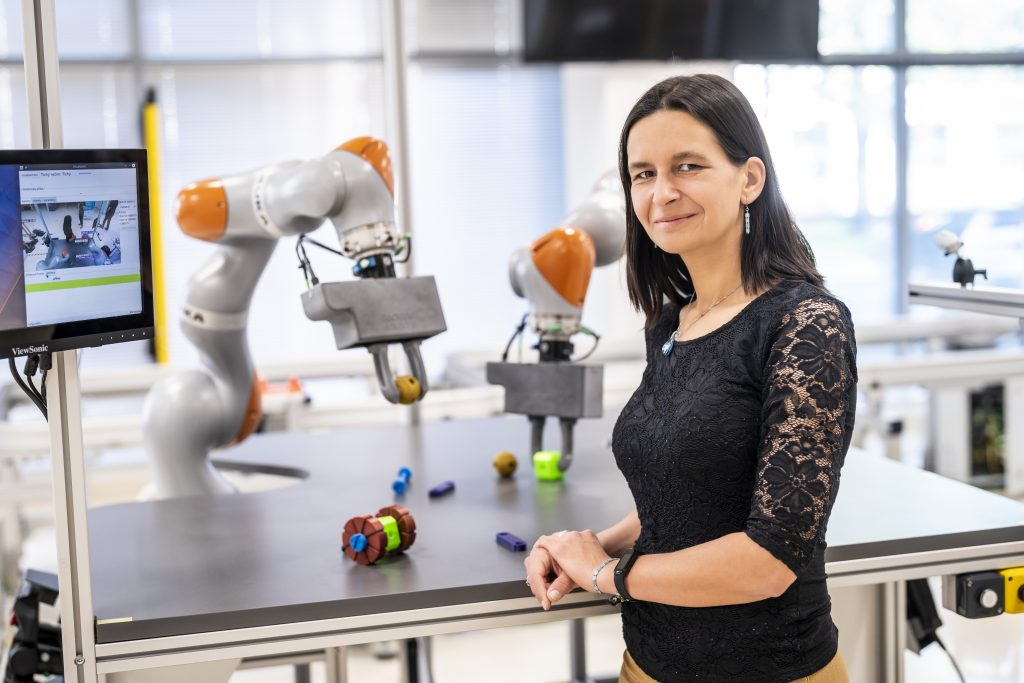

In this first edition of Women of ROBOPROX, a new interview format introducing women working on our project, we sit down with Karla Štěpánová, a researcher at the Czech Institute of Informatics, Robotics, and Cybernetics in Prague. As Head of the Robotic Perception Group, Karla is at the forefront of advancing how robots understand and interact with humans. In our conversation, we dive into her journey, her vision for the future of women in robotics, and how initiatives like the ROBOPROX Women Forum are playing a crucial role in shaping that future.

Karla, tell us a little about your journey. What inspired you to pursue this field, and what excites you most about your work?

I wouldn’t say I’ve been interested in robotics and artificial intelligence since childhood. I’ve always had many different interests and hobbies, and I was unsure about what my future career might be. I couldn’t decide whether to study philosophy, astronomy, mathematics, journalism, neuroscience… Everything seemed fascinating. In the end, I chose to study physics because it felt like a solid option for someone who was still uncertain about their future. Only after completing my master’s degree and having my first child did I finally have time to reflect on what I truly wanted to do. Watching my child begin to explore the world sparked something in me, and that’s when I discovered cognitive science and AI. I read a few books by František Koukolík, and everything suddenly clicked — this was what I wanted to pursue.

Cognitive science allowed me to connect all the sciences I loved with an understanding of human brain development. I became fascinated by the idea of modeling a natural autonomous system and learning how it develops. Having my second and third children only deepened my enthusiasm. How is it possible that all of this evolved? Since then, I have been trying to model and replicate what my children can do and learn so easily — without much success. The ability of natural organisms to adapt, develop, and communicate is incredible. How is it possible that each of my children has such a unique way of communicating, yet we still understand one another? Trying to uncover this truly fascinates and motivates me during long nights of research.

Can you share more about your current work and research? What are some of the key areas you’re focusing on at the moment?

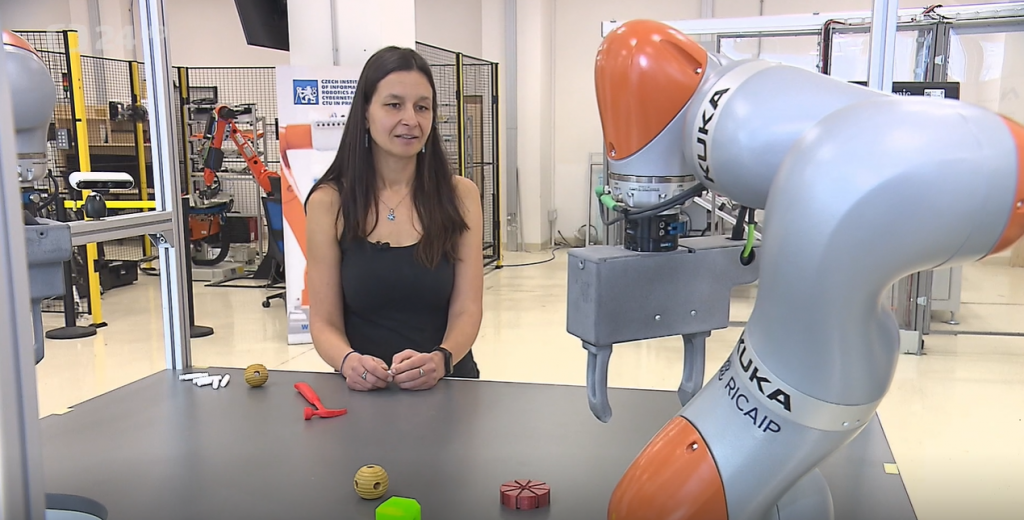

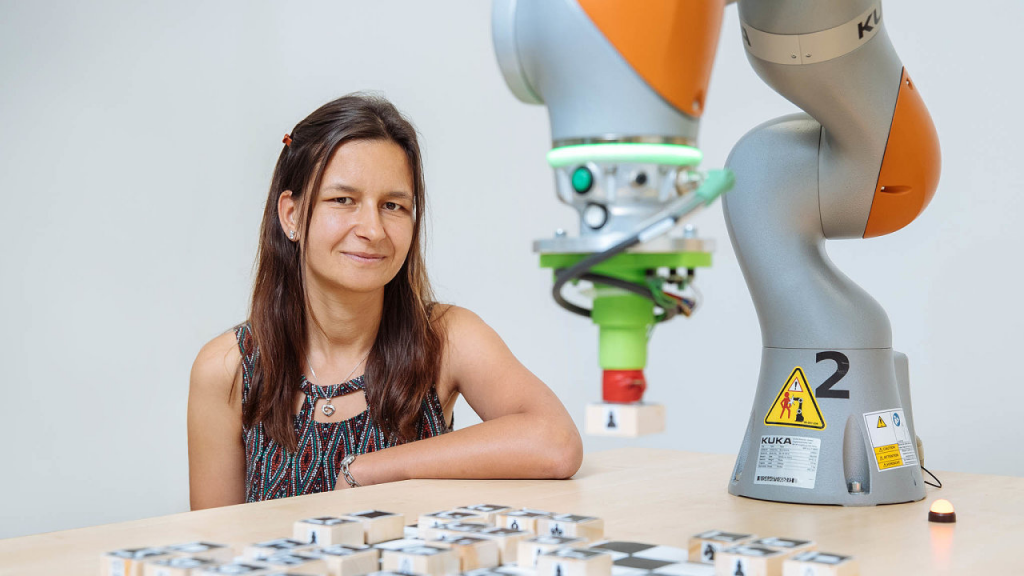

Currently, my main focus is on how we can communicate with robots both verbally and nonverbally, and how robots can understand the tasks we want them to perform. We aim to model this communication using both a deep multimodal neural network and a more analytical, probabilistic approach that integrates information from language, gestures, and the observed environment.

Since these signals are temporal and asynchronous, aligning them requires specialized algorithms capable of handling the challenge of limited data. Additionally, we consider the context of the situation —such as object properties and user profiles — when interpreting instructions.

Science often involves solving complex problems. How do you approach problem-solving both in your research and in your personal life? Do you see any similarities between the two?

I love planning, organizing, and tackling complex problems. Sometimes I get overwhelmed, but most of the time, I enjoy solving them. I often simplify complex problem-solving into a multi-criteria constrained optimization problem with random variables—both in my scientific work and personal life. Taking a snapshot of the current world and my beliefs about the constraints I face, I try to find the optimal decision.

For example, when planning vacations with kids, I consider factors such as distance, water availability, weather probabilities, access to civilization in case of emergencies, flight costs, the length of the trip each child can handle, necessary backpack size, and even the kids’ moods based on elevation changes. All of this runs in the back of my mind when deciding on the next summer vacation destination.

But real-life decisions are even more complex. Conditions constantly change, and new observations must be integrated into the decision-making process. While planning a vacation, I continuously update my considerations based on maps, kids’ comments, flight servers, friends, and trial trips at home and try to consider possible future changes in mood, health or weather. Similarly, in AI research, you must adapt to an ever-evolving landscape, as new papers appear every day, constantly shaping the direction of your work.

In general, when solving complex problems, the goal is to develop solutions that are optimal given the available information, robust against the most probable changes, and resilient to less likely but impactful disruptions. Mathematically, we could model this as a Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP) — which accounts for uncertainty, decision-making over time, and incomplete information which is what both AI research and parenting is a lot about.

As much as science and parenting share similarities, I would say research is far easier — because in science, I control many of the variables. In my personal life, I must handle different goals and inner models of the world held by other family members, which can be frustrating — especially when I strongly believe I’ve found the most optimal solution for the whole family. But that’s where another area of research comes in — game theory.

Could you tell us a bit about your role in the ROBOPROX project and how you’re contributing to its goals?

I work on human-robot interaction (HRI), focusing on teaching robots new tasks and developing a common framework and platform for HRI setups. Part of my work involves interactive perception, which enables robots to actively participate in exploring their environment rather than passively observing it.

And what are the main objectives of the ROBOPROX Women Forum, and how does it support women in robotics and related fields?

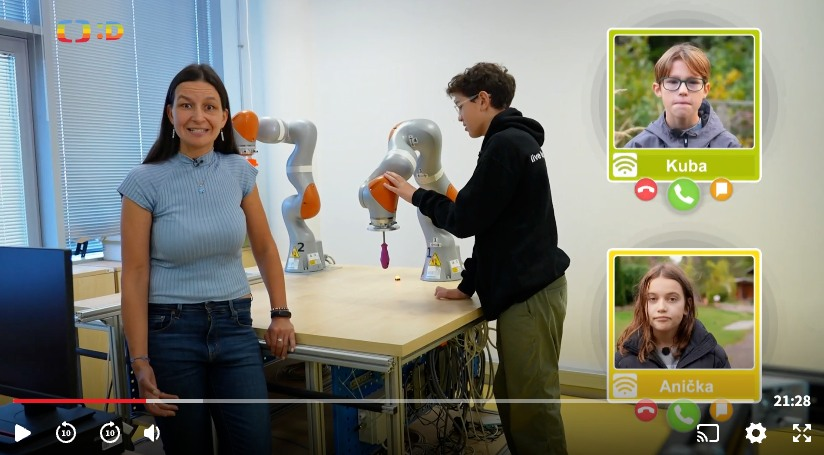

I believe that one of our main objectives in Women Forum is to make it clear to women that it’s completely normal to pursue robotics, manufacturing, and AI — that these fields are great places for girls and women to be today, offering engaging and exciting opportunities. As we know, it can be difficult to be a pioneer in male-dominated fields, so we strive to support girls through special scholarships, sharing information about existing groups and organizations, and highlighting success stories of women already in the field to motivate others to join.

What do you think are some of the biggest opportunities for women in robotics today?

I really don’t like differentiating between men and women, especially in research, as I believe it often does more harm than good. Robotics today is clean, safe, and not physically demanding, so there’s no reason why men and women shouldn’t be equally represented in the field. After all, the only things required are creativity and intellect. Furthermore, based on my observations, mixed teams consistently add value to research.

If I had to highlight some of the key areas where women might bring special value to a team, I would say that women often excel at organization and planning—likely because they handle complex real-life problems, gaining practical training that translates well into research. AI research today is one of the most complex challenges we face. Additionally, I’ve noticed that women are often skilled at bridging disciplines, which is essential for advancing AI and robotics. I also believe that many women (and many men as well) have a unique strength in understanding the social impact of robotics and AI on our daily lives. This perspective creates opportunities to model real-world scenarios, ensuring robots are safer, more robust, and more pleasant companions.

What have been some of the positive outcomes or successes of the ROBOPROX Women Forum, particularly in terms of mentorship, funding, or building a sense of community?

Thanks to the scholarship, we’ve received applications not only from faculties within ROBOPROX, but also from other faculties and even from abroad. Many of these girls applied for our scholarship and have now joined our teams. I also appreciate how the women within ROBOPROX are connecting and sharing their research. We also took part in some public events, for example Jindriska Deckerova is engaged in “Staň se na den vědkyní”, an interesting event for high school students. As for mentorship, I by myself must say that I’ve only encountered motivating and supportive male mentors, who have gone above and beyond the expected support within ROBOPROX and helped me a lot on my path to building a team and now a group. As for community building, it’s still too early to evaluate — let’s see in a few years.

Where do you see the future of women in robotics and computer science, and what progress would you like to see in the next few years?

I think that mixed teams of men and women are more likely to develop human-centered, less biased solutions. Right now, it often feels like we are being forced to adapt to technology rather than technology adapting to us, and in the process, we lose part of our humanity.

Our society is already full of technology and will soon be full of robots. As much as I would prefer to live life with less technology, if the technology has to be part of it, let’s make it at least not destroy us as people with soul. My vision is to develop robots that truly adapt to us, so we can feel satisfied and happy living alongside them. And I believe that women play an essential role in ensuring AI and robotics evolve in this direction.

What are you most excited about for the future of the ROBOPROX Women Forum? Any upcoming initiatives we should look out for?

We want to make a survey among all the involved universities in the ROBOPROX that will explore different perspectives on why women select specific careers and research paths. I am really interested in the results.

Looking ahead to your own career, what are you most looking forward to in the next phase of your work?

This year, we will be starting a major European project that will connect robotics with large multimodal models. While my experience with large models is still quite limited, I am thrilled about the opportunity to work with top research teams in this dynamic and exciting field, and to apply it to a robotics use case. I’m also really looking forward to our ongoing collaboration with the start-up RoboTwin — a start-up founded by the inspiring girl, Megi Mejdrechová, who has also conducted research with us and was selected this year by Forbes Česko for its 30 Under 30 list..

For young people considering a career in robotics or STEM, what advice would you give them? What is the one message you’d like to share with the readers?

Don’t expect to achieve everything immediately, but if you choose a path and commit to it — especially by diving deep into understanding math and algorithms — you can accomplish truly remarkable things. If you’re passionate about solving exciting, complex problems and want to see how your work can directly impact the lives of those around you, then robotics and STEM are the fields to be in right now.

And last but not least, what is your most memorable and enlightening “fuck-up” in your career so far, that has moved you forward?

I can definitely remember some big kicks to the bottom, but I actually believe that the smaller ‘fuck-ups’ are often more important — and how we deal with them matters most. In research, resilience is crucial. There are always those smaller setbacks that can move you forward, as long as you don’t let them break you. Whenever I feel completely unmotivated — when I’ve put in too much energy without success, when nothing seems to work, and when I just want to give up, with paper rejections piling up — it often comes down to pushing just a tiny bit more. Success is usually right around the corner. Sometimes, just stepping back and letting things be for a while can also work wonders.

About Karla

I am a researcher at the CIIRC CTU and the head of the Robotic Perception Group. My work focuses on developing AI-driven systems that enable robots to learn from human instructions and demonstrations. I am particularly interested in how robots can understand human intent and context by integrating data from multiple modalities using probabilistic models and multimodal neural networks.

I have been leading the Robotic Perception Group since 2024. I earned my Ph.D. in Artificial Intelligence and Biocybernetics from the Faculty of Electrical Engineering at CTU in Prague in 2017 and my Master’s degree in Condensed Matter Physics from the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics at Charles University in 2010.

My research interests include probabilistic models of cognition, unsupervised learning, multimodal integration, language acquisition, symbol grounding, learning by demonstration, and human-robot interaction.